Most English students dread reading one kind of literature the most: Shakespeare. Not only is it difficult to understand, but it is also difficult to teach. Ms. Christa Forster, an English teacher for ninth, tenth, and twelfth grade in the Kinkaid Upper School, strived to stop making Shakespeare text seem so “scary” to students.

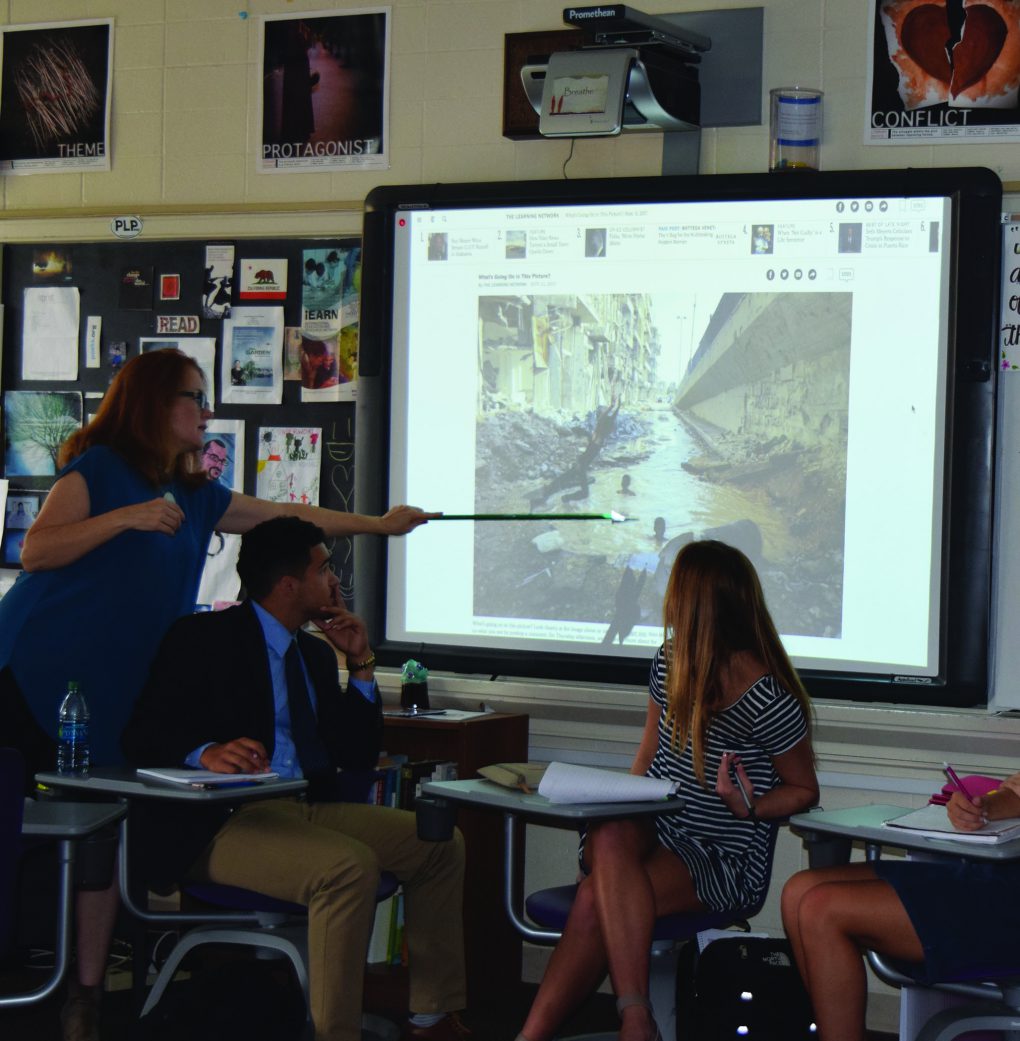

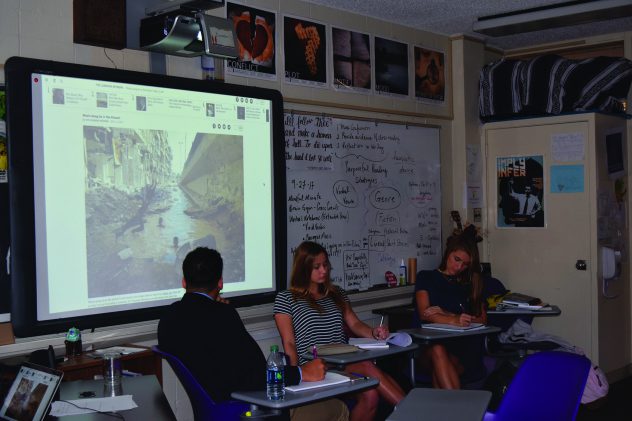

Ms. Forster uses the New York Times feature, “What’s Going On In This Picture?”(WGOITP), to improve their skills of critical analysis, close reading, and writing of evidence-based paragraphs, and hopefully assist students in transferring these skills over and applying them when reading their assigned Shakespeare text.

While doing this, not only did Ms. Forster gain the attention of students in her classes, students in other classes, and even other teachers, but she also gained the attention of a New York Times editor and writer, Michael Gonchar, who reached out to her, hoping to write an article on her unique teaching method.

“What’s Going On In This Picture?” is a New York Times feature, in collaboration with The Learning Network, where a seemingly random photo is posted, and viewers must try to figure out the context of the picture, and leave their best guess in the comments section.

Last school year, Ms. Forster began incorporating this feature into her classes. She would show her students the picture, and have them publish a comment containing an analytical paragraph of what they thought was going on in the picture.

“The [students] were practicing responding to the pictures, using analytical paragraph format, and they were getting their paragraphs published, and therefore seen by not just me, but ostensibly, the world,” Forster said.

Forster asked her students to answer three questions about the pictures they viewed, to help them properly analyze the photos. These questions that they used to analyze confusing photos may also be used to analyze confusing text.

Ms. Forster assists her students in relying on these three questions from Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), which are: “What is going on in this character/scene? What do you see in the text that makes you say that? What more can you find?”

Ms. Forster would reply to every one of her students’ comments with feedback on their analysis. She would comment back to each comment from one of her students, grading them on their analytical format in their paragraphs. She would then post their daily grades in the Live Gradebook, on a scale of one to ten.

All of these comments and replies Ms. Forster ended up gaining the attention of an editor from The New York Times.

“As we moderated posts to our WGOITP? feature, we noticed Ms. Forster regularly providing feedback on her students’ comments, so we contacted her to find out what she was up to,” wrote a reporter from The New York Times.

Ms. Forster was ecstatic when she recieved an email from an editor of one of her favorite papers.

“Maybe two weeks after we started [WGOITP]… I got an email from the New York Times editor, Michael Gonchar. He reached out to me and he said, ‘we noticed that you’re doing something really interesting… what are you doing and why are you doing it?’ …I got that email and I was pretty stoked that they had noticed we were doing this project, stoked that they noticed that the students were taking it seriously,” Forster said.

Ms. Forster believes that practicing WGOITP and the skills that come with it can be useful in many other aspects of life then just English.

“Because what it stengthens is students reasoning skills, those skills are necessary in every single subject. The other reason it’s applicable: any other teacher could use it. A science teacher, a debate teacher, whatever, even a coach, because the pictures come from news that is relevant to all of society. So, no matter how they end up, how a student ends up, in a football game, or in a math problem, they’ve also had this practice on something that’s relevant to their lives, because they live in society with other people,” said Forster.

Students also said that they enjoyed this activity in class, and they think it could help other students who do not practice this already.

“It may not be some kids cup of tea, but it’s a pretty fun activity. You get to be creative. [WGOITP] helped refine our critical thinking skills, and it showed us how to look at details in the bigger picture in context,” said Dani Knobloch (11), a student of Ms. Forster’s last year.

Ms. Forster noticed that her students experienced less of the anxiety and panic that happens when a student opens a book by Shakespeare and is unable to understand the language that is used. She believes this is because her students endured a similar experience, but on a smaller scale, when they had to look at a photo where they had no idea what was going on, and do their best to look closely and figure it out.

Ms. Forster wanted to begin working on her students’ critical analysis skills after all of the chaos preceeding and following the 2016 election, as they would become very vital skills during the uproar that followed this election in the media.

“After the election… I had this sense of urgency, that it was my responsibility to teach my students how to think critically. To be able to tell real news from fake news, to be able to make decisions that were formed on evidence, to be able to evaluate the evidence,” said Forster, “So I went to the New York Times, because I was thinking this is a paper that is respected real news without a doubt, and maybe they’ve got something for me to help me teach my students critical thinking skills… So, I found WGOITP… It was just a featured thing on the day I happened to go there. And I realized that it would help, [and] it would be fun,” Forster said.

Ms. Forster chose WGOITP as her way of teaching her students these skills, because it looked like it had an element of fun to it. She believes that in order to learn something efficiently, students must have fun, and she is always looking for a way to help her students have fun, or a way to make things a game.

“I believe that [learning] should be fun, I believe that it is fun. It’s super fun for me to learn new things, so I looked for things that I know have an element of playfulness and play and fun, built into them. Basically if I had to boil my pedagogy down, or my teaching philosophy down, to a nutshell, it would be that it’s essential to have fun while learning,” said Forster.