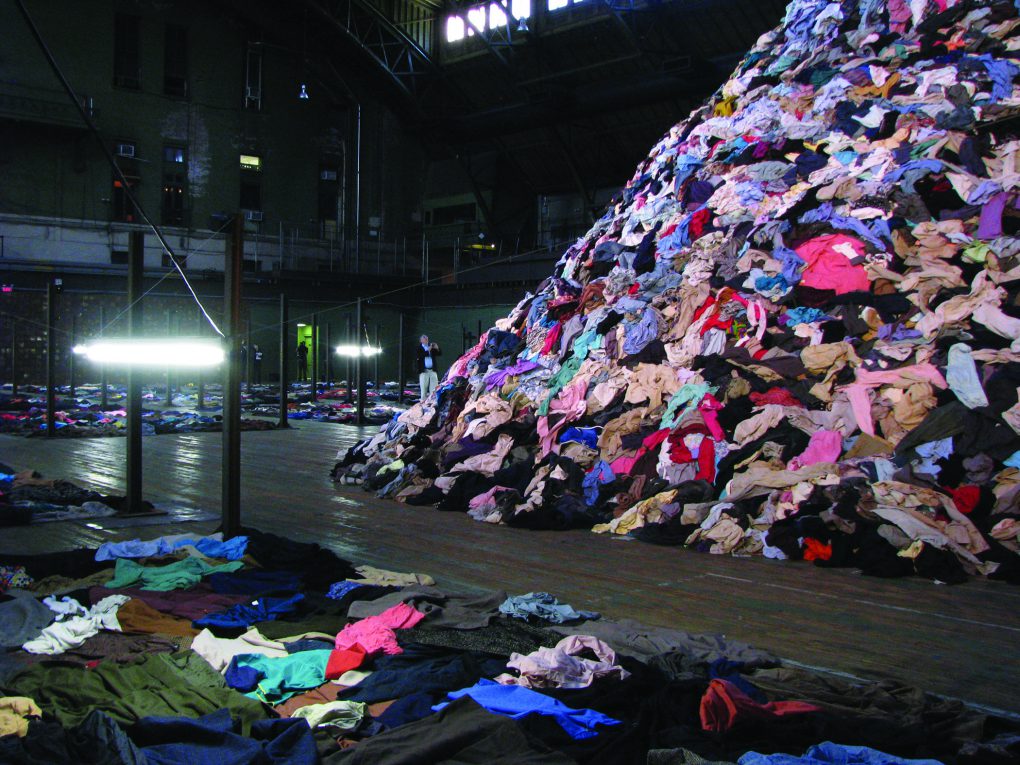

Harried workers struggle to rid themselves of the flood of unused items. Dirty sneakers, halloween costumes, Barbie dolls, used tea bags—the donations pile on top of one another in dingy mounds. The sheer size of the piles is depressing. This is the ‘second disaster.’

After every disaster thousands donate items for victims, but a lot of the time the donations simply go unused. The jumble of items becomes a silent monster for emergency management; most of the time the donations are thrown away.

Here in Houston, we have to learn from the mistakes of the past—we do not have room for a ‘second disaster.’

For example, according to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, thousands of second-hand clothing sat on a beach in Indonesia. And they sat for so long, they became toxic. Eventually local officials poured gasoline on the piles and set them on fire. The ocean took care of the rest.

Following the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary mass shooting in Newtown, CT, the town was barraged with 67,000 teddy bears. It sounds like a generous gesture, but Newtown’s total population is less than 30,000, so they were overwhelmed with so many toys.

“I think a lot of the stuff that came into the warehouse was more for the people that sent it, than it was for the people in Newtown,” said Chris Kelsey to CBS News in 2016, who worked for Newtown at the time. “At least, that’s the way it felt at the end.”

Herein lies the bigger problem.

People donate items because they like to feel they are making a direct contribution; it feels more personal. But there is a chance that their contribution will literally end up in a landfill. Our desire to help is actually harming those that are affected. We have to start to listen to what people need, rather than give what we think will be best.

“People don’t understand that we don’t need your dirty tennis shoes with your pinky toe sticking out,” said Ms. Branaman, the community service coordinator.

It’s uncomfortable to discuss, a harsh reality that our goodwilled efforts oftentimes hurt. Organizations are afraid to ask people to stop donating certain items for fear that they will stop donating anything, and NGOs that ask for only monetary donations are not usually successful.

We often say, “it’s the thought that counts,” but when we are faced with tragedy, we need more than just thoughts. Just telling people to give anything sets a low bar; it is important to give back in the right way. While there have been many failures in donation efforts, there have been a few successes as well. After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, relief efforts were organized by a group called Occupy Sandy. They created a sort of donation registry, so they would be able to convey to their donors which supplies they actually needed. Similarly, after Harvey, organizations large and small have used Amazon Wish Lists.

Individuals can take action as well. Many people rush to donate blood after a disaster; however, blood has a shelf life of 42 days so it is often tossed out when there is excess. Hospitals need people to donate blood year-round rather than in times of disaster, especially rarer blood types which they are frequently short of.

Canned food drives are also conducted not only after a disaster but often throughout the year. But donating canned food is impractical; according to a 2013 survey, fifty percent of all donated canned food is trashed usually because it’s expired or it’s already opened. Instead, donating money to food banks is more beneficial, since they can buy healthier, fresh produce for a much cheaper price.

Most of the time, in fact, donating money is one of the most compassionate things a person can do. It is even better than donation registries, as with money, organizations can buy supplies in bulk for a less amount of money. Fundraisers like JJ Watt’s, which raised more than $37 million before closing donations on Sept. 15, can be extremely successful. Organizations can use the money in ways that will be most helpful; donations are far less likely to go to waste than donating items.