[dropcap]T[/dropcap]en years ago on Aug. 23, 2005, a storm brewed over the islands of the Bahamas and blew right into the Gulf of Mexico. It gained speed and wind, until it tore through Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. And when Hurricane Katrina reached Category 5 status in the early morning, it ripped right through New Orleans, Louisiana.

Almost half of New Orleans is below sea level. Surrounded by the Mississippi River, Lake Pontchartrain, and swamplands, New Orleans was dependent on levees, the strong walls that kept water out of the city. The levees holding water from Lake Pontchartrain and the swamps weren’t sturdy enough to withstand Katrina. When they broke, water flooded almost the entirety of the city. Anyone who could leave fled the city, but their houses couldn’t leave with them. Homes were destroyed beyond recognition.

Like many others, Houstonians donated money and food. Being only a five-hour drive away from New Orleans, they also sheltered evacuees. Parker Browne (10) and Olivia Hart (11) are two students who moved from NOLA to Houston after Katrina.

Browne lived in Uptown New Orleans (“The Sliver by the River”) when Katrina struck, just two weeks after school had started again at St. George’s. He and his mother evacuated towards North Louisiana to stay with his grandmother.

“My most vivid memory is sitting at my grandparents’ house, and my entire family was hovering over the TV watching CNN. Anderson Cooper was reporting the storm,” he recalled.

Browne’s house was one of the lucky ones—it was still left standing—but he never moved back. He spent the rest of the semester in North Louisiana with his cousins before moving to Houston at the end of the year.

“We try to go back three or four times a year,” he said. “Not much has changed. The French Quarter changed a little bit, not much, but I feel that [the city] hasn’t changed; it has come back a little bit stronger than before.”

Hart also lived in Uptown New Orleans at the time. When her mother came to wake her on what was supposed to be the third day of school, she packed her suitcase instead of her backpack. “When [Katrina] hit, we evacuated to Baton Rouge to go to my step-grandmother’s house. There were two rooms, and eleven people living there because my entire family lived in New Orleans. I remember she had this tiny couch, and all eleven of us sat together watching one of those little TVs with the antenna, because the power was out in Baton Rouge. It was right when the levees broke, and my whole family was crying, but my cousin and I were young, so we didn’t really know what was going on.”

Hart’s house wasn’t damaged either, and she briefly moved back in. When her dad attended a business meeting in Houston, the family went with him and they never left. Hart spent her Labor Day weekend in the Crescent City, but she doesn’t visit as much as she used to because all of her family now lives in Houston. She wishes she could go more often because “it still feels like home to me, so we try to go up as much as we can.”

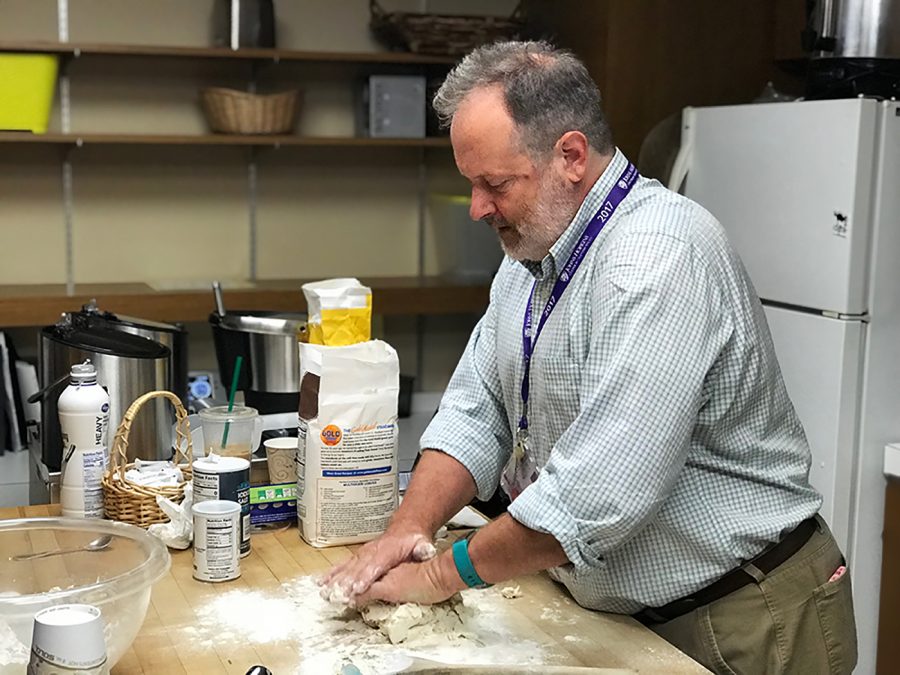

Another member of the Kinkaid community has ties to NOLA as well: Mr. Mark Sell, the Director of Technical Theatre who is in charge of building sets and operating lights at assemblies and theater productions.

In 2005, Mr. Sell was living in Seattle, Washington when he heard the news of Katrina. His two daughters set up a lemonade stand to raise funds for New Orleans. A couple of years later, his wife was reading an article about volunteering in New Orleans, and they were inspired to do the same.

“We went to New Orleans for a week [to volunteer], and it was amazing. We helped rebuild a house where an elderly couple lived. It was an amazing experience; I’d never worked so hard in my life,” said Mr. Sell.

In 2007, he made the decision to move to New Orleans and help out. Even two years later, the city still had much to rebuild. He began as a volunteer for the organization Project Homecoming and eventually became construction manager.

“When we went back home, we couldn’t stop thinking about New Orleans and what it needed. It needed people that could interface with volunteers; it needed people with construction and organization skills. There were tons of volunteers coming in, but it was Project Homecoming’s job was to teach these volunteers how to rebuild these people’s houses,” said Mr. Sell.

When asked what they all missed about New Orleans, they talked about the culture, the food and the Saints, but the one thing everybody missed was the people. The food is great, the culture is one of a kind, but the people are what you never forget. Hart said, “When you walk down the street in New Orleans, you know who everyone is, and they’re so open and friendly. I love [Houston and New Orleans] both, but I love the sense of community New Orleans has.”

Fast-forward ten years. The city has yet to finish the rebuilding process. Many people never returned to their homes after the hurricane, leaving vacant lots of rotting houses in the neighborhoods. Many people made their lives elsewhere.

Mardi Gras still happens annually; Café Du Monde still makes its famous coffee and beignets every day in the same style as when they started 153 years ago; jazz bands and street artists still occupy the French Quarter as they did before. Hurricane Katrina is a reminder that it’s so much harder to rebuild something than to destroy it.