[dropcap]I[/dropcap]magine yourself walking in the Galleria, minding your own business. You stroll into the Apple Store, checking out the new iPhone and MacBook Pro. Then you spend some time browsing various clothing stores. Next up is the Adidas store, where you grab a pair of new kicks. To finish the day, you head to the food court, where you enjoy a burger and frozen custard shake from Shake Shack.

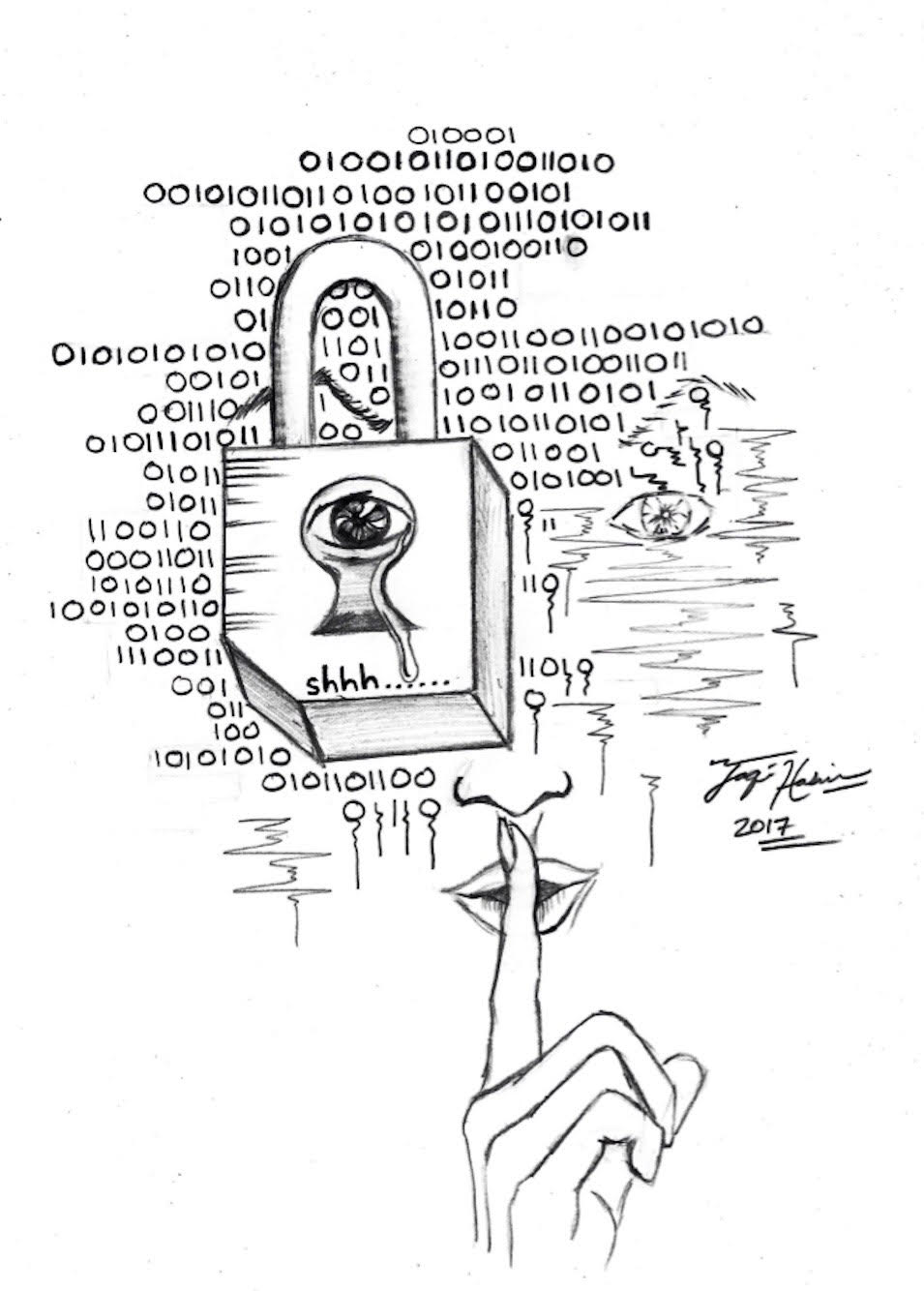

Now imagine someone was following you that entire day, taking meticulous notes of where you went, at what time you did so, what you looked at, how long you spent looking at it, what you bought, and every other specific detail imaginable. Imagine that this mysterious person took that information and sold it to someone else. How would you feel? Would you feel violated? This person may not be doing anything harmful to you, and you may not even know its happening, but does that make it okay? This scenario almost exactly mimics what internet service providers (ISPs)—like Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon—are now able to achieve thanks to recent developments in Congress.

Behind the commotion of the Russian interference in the 2016 election, there lies another huge battle in Congress that few Americans and even fewer students are aware of. In March, both the Senate and House voted in favor of a bill that would allow ISPs the ability to sell your browsing data to third-party companies. The bill, officially known as Senate Joint Resolution 34, would repeal privacy regulations previously created by the Obama administration’s Federal Communications Commission that required ISPs seek consent from customers to share their private data.

The Senate first voted to repeal the regulations in a narrow 50-48 battle, which was seen as a huge win for companies like AT&T, Comcast, and Verizon. When the bill moved to the House, Democrats attempted to counter Republican efforts by alerting the American public to the repercussions of the legislation. Sen. Chuck Schumer tweeted, “If bill passes House, your emails or history—including health & financal [sic] info – could be sold to 3rd parties w/ out your explicit consent.”

On Mar. 28, Democratic Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi linked this battle to the Russian interference in the election: “Americans learned last week that agents of Russian intelligence hacked into email accounts to obtain secrets on American companies, government officials and more,” Pelosi said. “This resolution would not only end the requirement you take reasonable measures to protect consumers’ sensitive information, but prevents the FCC from enacting a similar requirement and leaves no other agency capable of protecting consumers.”

Ultimately, the House voted 215-205 in favor of the Republican efforts to remove the broadband privacy regulations put in place by Obama. President Trump signed it into a law on April 4. Whether you are an ardent Trump supporter or a passionate liberal, a staunch Libertarian or a fierce Green party supporter, this bill crosses a dangerous line where your online privacy is invaded. Fifteen Republicans recognized the severity of the legislation and joined the 190 Democrats who voted against the bill. To put that in context, during the confirmation of Betsy DeVos—one of the most controversial cabinet nominations—two Republican senators voted to reject her. With that in mind and the fact that 15 Republicans voted against the repealment of these rules, it becomes even more clear how serious and nonpartisan this issue is and needs to be. ISPs will be able to access your browsing history–your personal, private information–and sell it to the highest bidder. This issue of broadband privacy transcends the partisan divide of our American government.

Republicans argue that this bill will put ISPs on the same playing field as websites; currently, companies like Google and Facebook derive their revenue from advertisers by selling user trends and information. However, ISPs have to seek permission from internet users to access and share private information with an “opt-in” program (users have to consent to allowing ISPs to access their information); websites, though, do not follow the same guidelines. The White House is making it easier for ISPs to access the same personal information. And this leads to another point: Is the government considering its citizens and consumers, or big businesses? Can Americans expect to see other legislation in the future lean towards the interests of lobbyists and major corporations?

For most students, a lot of the issues discussed and debated in Congress don’t really affect them: they don’t pay taxes, they don’t have to worry about healthcare or insurance, and the majority cannot even vote. However, this internet privacy bill hits close to home. We all use the internet. Every single day. Whether it be for homework, Netflix, asking Google a question, social media, or anything else you can think of, it plays a constant role in our lives.

Anna Thomas (11), who believes strongly in the citizen’s right to privacy, is “furious about” the bill. The bill, according to Thomas, “removes [her] ability to have a say in whether or not [her] information is sent to corporations.”

“What I do on the internet should remain my private information,” Thomas said. “If I consent to have that shared in any way, then the ramifications of that agreement are mine to bear.”

Thomas also thinks the nature of advertising will change, as “advertisements will become more pervasive and targeted.” She also finds fault with the fact that now, “anyone can learn anything about [her] without [her] knowing.” Thomas believes the bill will have a huge impact on her peers, who are heavy Internet users, more so than the adults who made the bill. She thinks people her age are “a huge demographic to which corporations will market products.”

As as a result of the bill’s passing, she has switched search engines to duckduckgo.com, which never tracks or records your search history. Furthermore, she has partially disabled cookies, stayed off certain websites that demand users agree to cookies, turned off location services on all apps except Google Maps, and is working on finding other ways to minimize her digital footprint. Thomas believes the value of the steps far outweigh the inconvenience of them.

“You have the right to privacy,” declared Ayush Krishnamoorti (9) with regards to the bill. Krishnamoorti, who was unaware of the fight in Congress over the regulations, believes the actions to eliminate these regulations are simply unjustified and detrimental.

On the other hand, Krishnamoorti argued, if this action was to bolster homeland security for example, he could understand: “If they want to investigate [users] for purposes related to terrorism, it’s okay, but selling [private information] is wrong.”

For Krishnamoorti, it’s also a matter of privacy between a consumer and a company: “You have trust in your company, and they shouldn’t be selling out your information.”

Mr. Harlan Howe, Upper School Computer Science teacher and Technology Director, believes “there are things to be concerned about” with the legislation. He understands why telecom companies were trying so hard to push this bill as it is in their best economic interests, however, Mr. Howe brings up a good point: While you can opt-out of these kinds of services on the websites of companies like Yahoo, Google and Facebook, “you can’t really opt-out of your ISP, especially if they’re the only ISP in town.” However, because the data collected will be largely anonymized, and there will be some safeguards to keep your privacy, his browsing habits will not change.

“Keep in the back of your mind—this is true in most cases—when you’re on the internet, everything you’re doing is public: not just what you’re posting but where you’re clicking, on campus or off campus,” Mr. Howe said.

With regards to the telecom industry’s interest in the bill, Mr. Howe believes ISPs “are already charging money for the service: this is another revenue stream they want. They’re trying to enter a new market to compete with Google and Facebook.”

This bill and debate, Mr. Howe thinks, will also continue to lead a conversation of other Internet issues, including net neutrality and the question of whether ISPs “are utilities or a business.” These issues will continue to “bounce back and forth” and will “be one of the big questions for some time: how is data used, who gets to use it, how do we access it, and how transparent is the process?”

Our privacy online, which some would argue is equally as important as that in real life, has been altered in a way that may not visibly change in the immediate future. What should have been a nonpartisan issue wherein elected representatives voted to protect the privacy of users/citizens turned into a matter exploited by the influence of lobbyists, big business, and greed. But worst of all, many Americans were unaware of the battle in Congress and unaware of the President’s signing of the bill into law.